»On the Ethos of Concrete Art«

written by Eugen Gomringer, 2002

There are abundant examples attesting to the thesis that over the past ninety years concrete art, more than any other art, has been accompanied and motivated by moral claims of an apodictic character. Hans Arp, in his manifesto of 1915 wrote: »Such works are constructed of lines, surfaces, forms and colours which strive to move beyond the perspective of the merely human to the infinite and the eternal. They thus seek to relinquish the standpoint of the ego.« He continues: »Concrete art endeavours to change the world and render it more bearable. It strives to free man from perilous madness and vanity, and to simplify life. It aims to attune life to nature.«

When concrete art finally realized its idea, it was frequently compelled to withdraw into an inner exile under the constraints of the National Socialists. However, in Switzerland it continued to flourish; although, even in Switzerland, where it had become considerably more pragmatic in Max Bill’s and R.P. Lohse’s theories, it fully established itself only by drawing on postulated eternal values. In one of the bulletins of the »Galerie des Eaux Vives« in Zurich, devoted to concrete art between 1944 and 1945, Socrates and Plotinus are referred to as the forefathers of the values of simplicity, beauty and the hidden quiet harmonies of the soul.

After his studies at the Bauhaus, one of the figures who was to develop further the principles of Kandinsky and Mies van der Rohe was the Munich-based artist, Rudolf Ortner. The spirit of his work, still alive today, was grounded in classical constructivism, as is indicated in the invitation to an exhibition at Villa Stuck in Munich in 1991: Ortner, »concentrates less on surfaces than on the three-dimensionality of architecture. His concern is to explore space, to feel and to design …«.

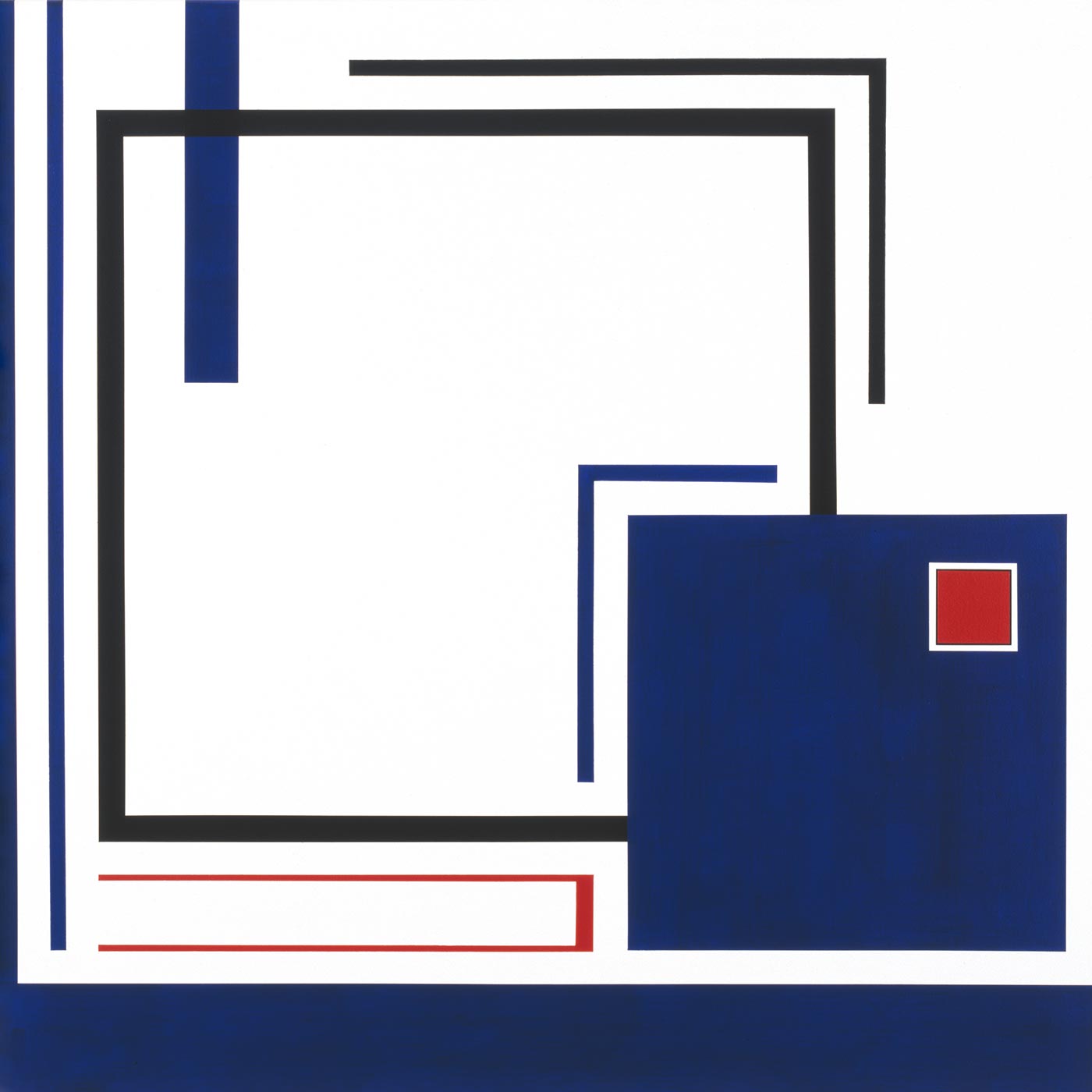

These and other such remarks come to mind in the paintings of Ina von Jan. The artist fully recognizes the moral and compositional principles of concrete art and has made them her own. That she draws on some of the elements and methods of her artistic mentor Rudolf Ortner is clear. At the same time, however, the uniqueness of her own creations is also evident. What strikes the viewer as especially impressive is the particular conviction and sense of purpose with which Ina von Jan has appropriated the original works of concrete art, as exemplified by Hans Arp. The persisting uncertainly, drawn out over decades, as to whether concrete art is still capable of representing purity and truth, should thus no longer be an issue – as indeed always happens when the principles of this art are seen afresh. In such rare cases, morality and the concrete art associated with it are consonant once and for all.

Yet, as an art form, it is important that it prove itself in aesthetic practice, that is, both in conception and design. With a characteristic inner conviction, Ina von Jan has focused on black and white, yellow and orange, red and blue. It is interesting to note the manner in which she has adopted the line and the »architectonic« surfaces of Rudolf Ortner and yet, in doing so, has still achieved a unique visual structure in her paintings. The almost life-like architectural elements, frequently integrated in the works of Ortner, are no longer apparent in von Jan’s work. What she has partially adopted is the three-dimensional effect. As a rule, the structure of her work comprises coloured surfaces and open linear features. The uneven thickness of lines and framed surfaces in neighbouring colours fix the accents of »breath«. What distinguishes her work from that of her mentor, Ortner, is the rectangular structure and her preference for the square.

Observers of the development of constructive concrete art have repeatedly focused on a certain isolation of the movement. Thus, they are taken aback all the more when new and convinced practitioners, such as Ina von Jan affirm this art form. What is remarkable about variants such as hers is the transcendental character of her composition as, for many years, this kind of conception was not originally included in the various programmatic statements of the movement, such as those of Hans Arp.

© Eugen Gomringer. 2002

Translated by Justin Morris